A few days ago, I had the opportunity to share with my colleagues what I actually do as a learning designer. I framed my talk with a metaphor – I imagine each course as a magical potion. And that potion is created in a cauldron into which I add various ingredients – models, approaches, and insights that help create truly effective learning.

Right after the talk, several colleagues came to me saying they’d like to know more. And so, this article was born. In it, I share how I think about learning – not just as a digital skills designer, but as a person who deeply cares about learning having real impact.

I can’t possibly pour everything from my head into one article or a short talk, but I’ll try to offer at least a small tasting spoon.

It’s Not Enough to Tell Them Where to Click

Many corporate digital skills trainings focus on instruction – showing people, step by step, how to do something. But that’s often not enough. It’s not enough to know what’s right. It’s not enough to have a manual. It’s not enough to say, “click here.”

For real behavioral change, we need more than instructions. We need to understand why we’re doing something, try it out, connect it to our own experience – and most importantly, start doing it automatically, because it makes sense to us.

That’s where learning moves into the realm of behavior change, and learning design intersects with change management. The goal of learning design is not just information transfer – it’s a real trigger for transformation.

Before I Even Start Cooking: A Design-Based Approach

When I design a course, I don’t start with methods. I start with needs.

A design approach to education works much like in any other field – the first step is to understand:

- The needs of the target group – What can’t the learners do yet, or what are they not doing that they need to change? What’s frustrating them? What do they want to shift?

- The purpose of the course – What do we want to change in their practice? What should be different after they go through the course?

- Concrete learning goals – Defined holistically using the KSA model and Bloom’s taxonomy.

Only after that comes:

- Choosing methods and formats – e-learning, workshops, blended learning, case studies, discussions…

- Designing specific activities – what the participants will experience, do, try out.

- And of course, designing impact measurement – How will we know something actually changed?

Ingredients in My Cauldron: Models and Approaches I Use

Every course is like a magic potion. My colleagues – digital technology experts – add a solid foundation: up-to-date, expert content. The content team sprinkles in flavor – tone of voice, engaging visuals, playful copy. And me? I throw in a handful of mysterious herbs that trigger transformation in the learner – methodology, thoughtful sequencing, and the invisible “how and why” behind the learning process.

Let me show you a few of these herbs:

🧠 KSA: Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes

If we truly want people to learn something, it’s not enough to just tell them what they need to know. We need to address all three levels:

- 📘 Knowledge – theoretical understanding (e.g. “I know I shouldn’t input sensitive data into AI tools.”)

- 🛠️ Skills – practical ability (e.g. “I know how to anonymize data in Excel, feed it into an AI tool, and use the right prompt for analysis.”)

- ❤️🔥 Attitudes – the learner’s mindset, motivation, and habits (e.g. “I not only know I should anonymize data – I actually want to do it.” Or: “It feels natural to use AI tools because they save me time.”)

When measuring impact, I don’t just ask whether someone knows the “correct answer.” I ask whether they can – and want to – do something differently.

🔄 Cycle of Experiential Learning

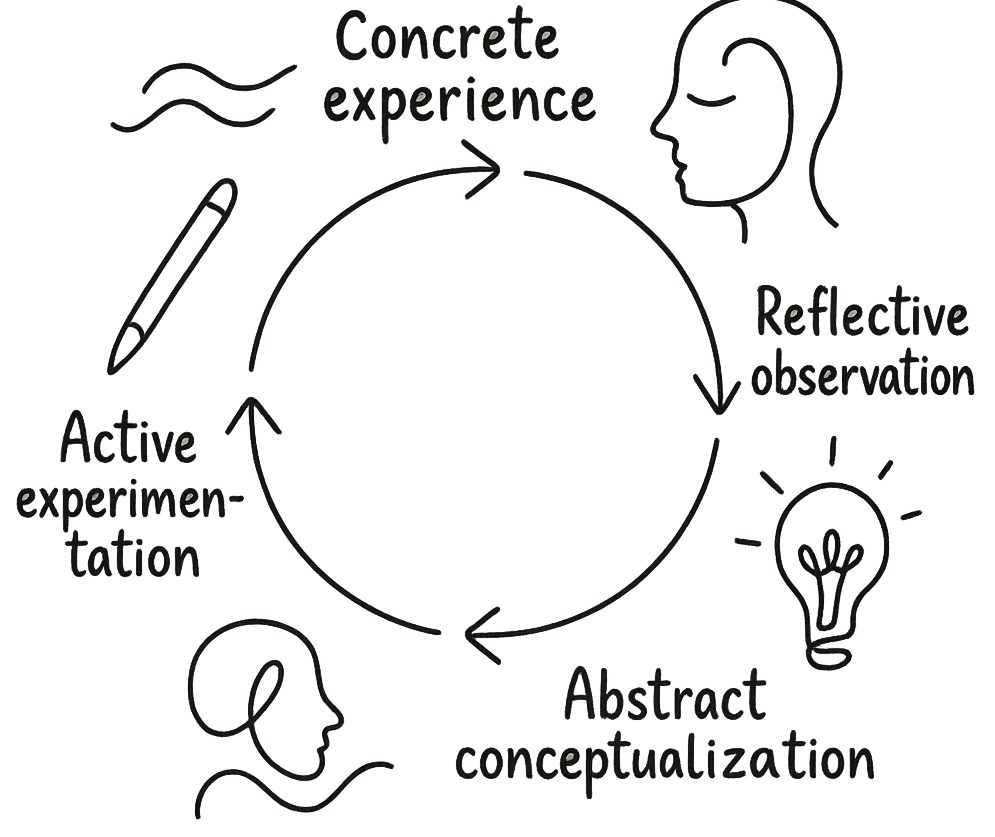

David Kolb described learning as a cycle – a natural process we go through when we truly learn something. It consists of four phases:

1. Concrete Experience – you try something yourself. For example: planning your first meeting, which then turns into chaos.

2. Reflective Observation – you think about what happened. What worked? What didn’t? Your mind asks: “Why did that fail?”

3. Abstract Conceptualization – you look for frameworks to make sense of it. You might read that meetings rarely go well without a clear agenda.

4. Active Experimentation – you try again, but differently. This time, you prepare an agenda, assign roles – and see the result.

What’s great? This isn’t just a learning method – it’s what we do all the time: when learning to cook, becoming a better team leader, or mastering a new tool.

That’s why this model is so useful in learning design. A well-designed course should guide us through this cycle – give us an experience, help us reflect, offer theory, and support a new attempt. The phases don’t always follow in order, but they all deserve space.

👥 Learning Styles (Honey & Mumford)

Inspired by Kolb, this model suggests that each learner tends to prefer a certain phase of the learning cycle:

- 🔥 Activist – thrives on action. Loves to jump in, try things, figure it out on the fly. Gets bored with long lectures. Learns best through role-playing, discussions, group challenges, case studies.

- 🪞 Reflector – a quiet observer. Needs time to process before speaking or acting. Learns best through journaling, small-group sharing, and time to think.

- 📚 Theorist – loves structure and systems. Needs to understand the “why.” Enjoys frameworks, models, summaries, and clear agendas.

- 🧩 Pragmatist – wants usefulness. Needs to see how the learning applies in real life. Prefers checklists, examples, simulations, and hands-on activities.

According to Honey & Mumford, these styles are evenly spread across society. And in my own workshops, every time I ask participants to choose their style, the distribution is… almost always 25% each. Though it shifts with the audience: schoolteachers tend to be pragmatic (“What can I use in tomorrow’s class?”), academics lean theoretical (“Is there a model for this?”).

Important: these styles are not boxes. They’re filters. Early theories assumed your learning style was fixed for life – but later research, like Coffield et al. (2004), showed otherwise. People adapt. We learn in different ways depending on the context, motivation, and environment.

Still, the model is incredibly helpful in course design. It reminds me to ask: “Is there something here for activists? For reflectors? For theorists? For pragmatists?” By honoring all types, I create a learning space where everyone finds a way to connect – even if it’s not their default preference.

🧩 SCARF model of Psychological Safety

Why does emotional safety matter in learning? Neuroscience has the answer: if we don’t feel safe, we can’t learn well. When our brain detects threat – embarrassment, judgment, lack of control – it triggers the amygdala, and we go into fight-flight-freeze mode. Our prefrontal cortex, responsible for reasoning and learning, shuts down.

David Rock’s SCARF model (2008) describes five domains that affect our sense of safety – and they’re all on a spectrum. We can either reinforce or undermine each one.

- 👑 Status – Do I feel respected and capable?

- Boost it: Acknowledge people’s contributions. Celebrate effort and presence.

- Harm it: Say “everyone should know this by now.” Ignore achievements. Mock mistakes.

- 🧭 Certainty – Do I know what’s happening?

- Boost it: Clear structure. Set expectations. Share the agenda.

- Harm it: Sudden changes. Lack of explanation. Ambiguity.

- 🕹 Autonomy – Do I have choice?

- Boost it: Let people choose topics, pace, tasks. Allow opting out.

- Harm it: Micromanagement. No flexibility. Strict rules.

- 🤝 Relatedness – Do I feel I belong?

- Boost it: Group work, shared stories, personal connection. Show your human side as a facilitator.

- Harm it: Isolation, mockery, rivalry. Acting like a flawless expert.

- ⚖️ Fairness – Do I feel it’s fair?

- Boost it: Clear rules, equal treatment, transparency.

- Harm it: Favoritism. Inconsistent feedback. Unfair evaluation.

Thanks to SCARF, I never skip over the opening of a workshop or the atmosphere. I go out of my way to show I care about the participants, that we’re partners. I explain what’s coming, stay nonjudgmental, and above all – stay human.

I’m learning to carry these same principles into asynchronous online content, where human connection is harder but no less important.

More Ingredients I’m Exploring

Beyond the models above, I’ve been experimenting with other influences that shape how learning works:

- Business mindset – How to connect learning with business goals and numbers. This is new to me – I come from the nonprofit world. But I’m learning about the Kirkpatrick model, ROI, and how to apply these ideas even outside business.

- Psychology of change – What stops people from doing things differently? How can we help? I’m diving into change management and the ADKAR model. It’s challenging – and exciting.

- Game-based learning – How to make it fun and immersive. In May, I joined a training in Estonia and I’m still digesting everything.

- Experience design – How to create emotional journeys that help learning stick.

- Online learning psychology – How people behave in asynchronous settings. What makes it easier or more enjoyable?

These are the spices I want to keep adding to my learning cauldron – to make our courses make sense, feel good, and actually work.

Synthesizing the Ingredients – Cooking with Heart

So let’s stir the pot:

- KSA gives me a framework for learning goals – not just what people know, but what they can do and how they feel about it.

- Kolb & Learning Styles help me design activities that suit different types of learners and guide them through a full learning process.

- SCARF reminds me: emotional safety isn’t a bonus – it’s the foundation for learning.

- Design thinking says: Don’t start with the method. Start with the need.

And there are so many more ingredients waiting to be discovered.

Learning design is a lifelong learning process.

It’s not just a craft. It’s also a feeling. Sometimes improvisation. Sometimes intuition. Always – care.

Just like a great chef knows that you can’t cook by recipe alone – that you must taste, adjust, and be attuned to your guests – a good learning designer must listen. To the learners’ needs. Their emotions. Their environment. Their limits and hopes.

Stejně jako dobrý kuchař ví, že nestačí jen přesně odměřit ingredience – ale musí i ochutnávat, ladit, být pozorný k tomu, co hosté potřebují – i my jako designéři vzdělávání musíme být vnímaví. K potřebám studujících. K emocím. K prostředí. K limitům i možnostem.

And just like a rich stew needs time and heat to develop flavor, real learning doesn’t happen with a snap of the fingers. But when it does – it’s delicious. And people come back for seconds.

Want to Learn More?

Hiim, H. & Hippe, E. (2001). Planning, Implementing and Evaluating Instruction

Julie Dirksen – Design for How People Learn –

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning

Honey, P. & Mumford, A. (1986). The Manual of Learning Styles

Coffield, F. et al. (2004). Should we be using learning styles?

Rock, D. (2008). SCARF: A Brain-Based Model for Collaborating With and Influencing Others

Anderson, L. W. & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing